In celebration of Black History Month, we are highlighting Cesar Chavez and the farm worker movement’s deep roots and successful collaborations with the Black Panther Party and African American activism in Oakland.

Before starting to build what became the United Farm Workers in 1962, Cesar helped organize and lead the Community Service Organization, California’s largest and most effective Latino civil rights group in the 1950s and early ‘60s. The first CSO chapter Cesar organized on his own was in West Oakland around 1953.

Founded in Oakland in 1966, The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was ideologically rooted in Black Power, self-determination, and the right to defend oneself against oppressive systems. It quickly gained the trust and respect of Black community members thanks to its Community Survival Programs such as free breakfasts, health clinics, food banks, health clinics, and more.

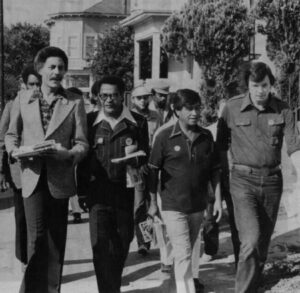

Greeting young African American children in Oakland (from left) Cesar Chavez, Bobby Seale, and Chavez aide Richard Ybarra.

In its early years, the UFW organized farm workers by providing them with services such as a credit union, death benefit insurance, a service station where migrants could buy cheap gas and fix their cars, and service centers to help them with myriad problems. Cesar and his colleagues believed workers weren’t just workers. While only a union could remedy abuses in the fields, workers faced other crippling dilemmas when they returned to their communities. So, it would take more than a union to overcome those dilemmas; it would take a movement.

Black Panther founders and early leaders Bobby Seale and Huey Newton emphasized dismantling systemic injustice. By focusing on the laws, bureaucratic structures, and economic incentives that maintain white supremacy and capitalism, they strove to dismantle them from the roots.

Meantime, from the UFW’s inception, Cesar Chavez inspired farm workers to challenge and overcome a farm labor system in this country that treats them as if they are not important human beings—as if they are beasts of burden—through self-organization and collective action.

Those visions perfectly positioned the Panthers and the UFW to share a commonality of missions and led them to support each other’s struggles.

Walking precincts in West Oakland in the mid-1970s (from left) U.S. Rep. Ron Dellums, Alameda County Supervisor John George, Cesar Chavez, and Assemblymember Tom Bates.

The Panthers joined the UFW’s international boycott of California table grapes in the late 1960s by picketing major supermarkets in Oakland. They supported farm worker boycotts of grapes, lettuce, and Gallo wine in the early-to-mid ’70s. The party refused donations to its free breakfast program from boycotted stores and organized carpools to shuttle shoppers to other markets.

Cesar and the UFW campaigned to send Ron Dellums to Congress in 1970, the first African American ever elected from Oakland. Cesar and the farm workers worked with the Panthers in Bobby Seale’s unsuccessful 1973 run for Oakland mayor, and in 1977, they helped elect Lionel Wilson, the first African American mayor of Oakland. Cesar walked precincts in West Oakland alongside African American elected officials.

Throughout their decades-long connection, each organization supported the other. The inspiration from their model of multi-racial solidarity is perhaps more relevant in this time of increasing polarization and ideological entrenchment. Their alliance is a reminder that authentic coalition building is possible when we connect through a larger shared vision for systemic change.

Would you like to know more about Cesar Chavez’s legacy? Please visit the National Chavez Center, an organization that is committed to promoting and conserving the memory of Cesar Chavez through his words and images, and the place where he lived during the last quarter century of his life – the César E. Chávez National Monument.