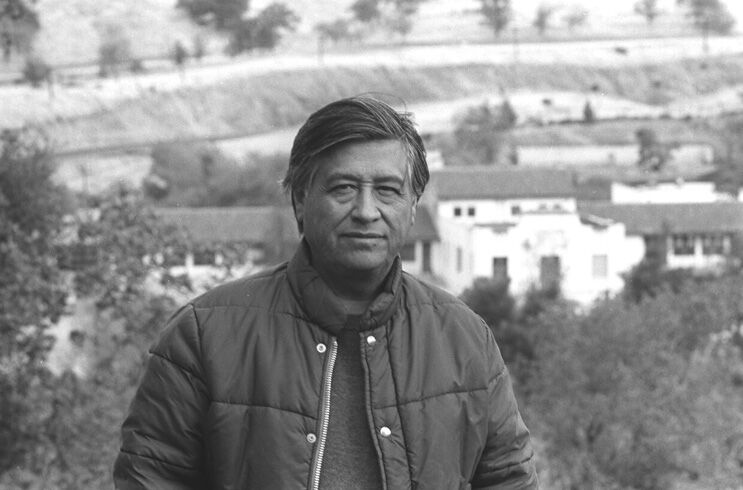

In honor of Latino Conservation Week, we sat down with the National Chavez Center’s (NCC) Executive Director Andres Chavez to learn about the NCC’s role in preserving the legacy of Cesar Chavez and the importance of landmarks that have been paramount for the Latino civil rights movement.

What is the role of the NCC in preserving Latino history and places?

The core of our work at the National Chavez Center is preserving Cesar Chavez’s legacy and ensuring its relevance. Cesar is the most recognizable Latino civil rights leader of the 20th century. The impact of the farm worker movement he founded and helped inspire extends well beyond the fields. What people saw in Cesar and the farm workers was that with hard work and determination, anything is possible. He said the movement sent out a message to all Latinos that if farm workers could bring change to the fields, it could happen anywhere. Preserving and telling this story is important and necessary because it’s an important part of America’s story. In 2012 the César E. Chávez National Monument—where my grandfather lived and labored his last quarter century at the Tehachapi Mountain town of Keene, Calif.—became the 398th unit of the National Parks Service. It’s the first and only national monument honoring a contemporary Latino figure. Our hope is that this national monument is the first of many to tell the story of Latinos in this nation.

Cesar Chavez is considered a forefather of environmental justice. What part of your grandfather’s legacy are you hoping to cultivate at NCC?

Most people know my Tata Cesar for his work organizing farm workers. Relatively few know about all of his other endeavors and interests. My Tata was a fascinating and complex person with an eclectic curiosity. This is best seen in the library of his office at the Chavez National Monument. The diversity of subjects and titles is incredible. Part of our plan is telling the world more about the Cesar we know. For example, sharing with folks his love for classic jazz music, about how he daily practiced yoga and meditation and his work as a social entrepreneur, just to name a few. His work in environmental justice is certainly an area we want to share more about. For example, the first time DDT was banned in the United States was not by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the mid-1970s, but in United Farm Workers’ contracts with wine grape growers in the late 1960s. My Tata’s last and longest public fast, of 36 days, was in Delano in 1988 over the pesticide poisoning of farm workers and their children.

Why is preserving Latino history through stories and historical landmarks and monuments important?

The mission of the National Park Service is to tell the story of America. Yet former U.S. Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar said the story of America couldn’t properly be told without also telling the story of Latinos in America. That’s why Secretary Salazar helped convince President Obama to establish the Chavez National Monument in 2012. That is why it is so important to share more of the diverse history of Latinos with all of the American people—and to get students and others to visit these historical sites.

What is the significance of the National Chavez Center site at Keene?

The National Chavez Center in the Tehachapi Mountains town of Keene, California, had an incredible history prior to when my Tata Cesar and the farm worker movement stepped foot on the grounds. As a kid, I remember running around the 187-acre property and coming across boulders with grinding stones carved into them. Later, I learned the indigenous people of the Kawaiisu tribe lived in and around the area. The site was later owned by the County of Kern and was home to the Stony Brook Retreat, a tuberculosis sanatorium. In 1971 the site became the headquarters of the farm worker movement and was named by my grandfather Nuestra Senora Reina de La Paz (Our Lady Queen of Peace), commonly referred to as La Paz. Interestingly, my Nana Helen Chavez had lived there as a child. She was treated poorly there, so when Tata Cesar wanted to move there, she initially refused.

My Tata’s life was filled with conflict. La Paz was where he began building a community of fellow movement members and volunteers who worked with him full-time for social justice. It became a spiritual harbor for him and other movement staff, who were “paid” $5 a week (doubled to $10 a week in the late ’70s) plus room and board. La Paz offered them respite from tough struggles in the fields and cities. You can learn more about the story by visiting the Chavez National Monument and watching the video in the Visitors Center.

Does NCC consist of any other places?

The National Chavez Center owns and manages two historic properties, the NCC in Keene and the historic “Forty Acres” complex outside Delano. The Forty Acres, in Delano, where the movement was founded and where it was headquartered until 1971, includes a co-op service station where farm workers could buy cheap gas and repair their vehicles, a health clinic, movement offices, a union hall, and the Paulo Agbayani Retirement Village finished in 1974 for elderly and displaced Filipino farm workers with no decent place to live their final years.

Does the NCC advocate to preserve Latino heritage?

Most recently, I testified before Congress in support of H.R. 8046, which would establish a Cesar E. Chavez and Farm Worker Movement National Park in California and Arizona. The NCC works closely with the National Park Service in developing exhibits and programs around the farm worker movement and interpreting its significance for Latinos and all Americans. We have testified and lobbied for state legislation honoring the Filipino farm workers’ contributions to farm labor history, including establishing a Larry Itliong Day in California on October 25 of each year. In 2011 the National Chavez Center hosted Telling America’s Story: American Latino Heritage Initiative La Paz Forum. At this forum, folks from National Parks Service superintendents from across the country gathered to discuss the role of Latinos in American history.

As executive director of the National Chavez Center (NCC), Andres Chavez, 28, leads the arm of the Cesar Chavez Foundation that educates and promotes his grandfather’s legacy across the nation. He also oversees two historic properties, including La Paz in Keene, Calif., where Chavez lived and labored his last quarter century, a portion of which is now the César E. Chávez National Monument that the NCC manages in partnership with the National Park Service.